Over at Joystiq.com, Jessica Conditt poses a very interesting question…

What happened to all of the women coders in 1984?

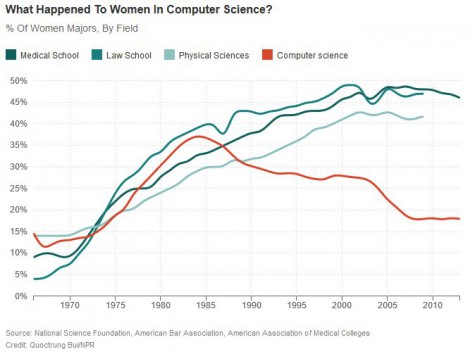

In 1984, women stopped pursuing Computer Science majors at American universities. From 1970 onward, women had composed an increasing percentage of Computer Science majors, but something happened in 1984 and that number began to drastically fall, an occurrence at odds with other tech fields. This trend has continued into the 2000s, and today women make up roughly 20 percent of Computer Science majors, as opposed to the 1984 high of about 37 percent.

To go with that question we have a graph generate by NPR’s Planet Money team (Caitlin Kenney and Steve Henn) which does appear to provide a stark illustration of the trend she’s referring to:

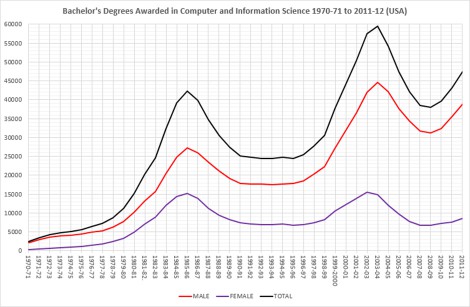

On the face of it, we do appear to have a significant drop off in the numbers of women taking, and completing, computer science degrees, as a percentage of total number of degrees awarded in that field, in the United States from 1984 onwards but that doesn’t necessarily mean fewer women computer science graduates overall. That trend could conceivably be telling us only that there has simply a rapid expansion in the number of male computer science graduates since 1984, far more so than for women, but not necessarily a fall off in the raw numbers of female graduates, so to be absolutely clear as to the precise nature of this trend I tracked down the original data set from the US National Center for Education Statistics and plotted a graph which shows the gender breakdown in Bachelor’s degrees awarded in Computer and Information Science between 1970-71 and 2011-12.

Okay, so that gives us a slightly more complex and nuanced picture of the relevant trends over time, one which shows that there’s rather more going on here than simply the sudden and unexpected disappearance of a generation of women coders.

Okay, so that gives us a slightly more complex and nuanced picture of the relevant trends over time, one which shows that there’s rather more going on here than simply the sudden and unexpected disappearance of a generation of women coders.

What we have here are two very clear spikes in the long term trend for both men and women with a fallow period in between spanning the period from 1991 to 1997 together with what looks to be the start of a third spike, which being 2009 to 2010, so there’s a cyclical pattern to be understood if we’re to make sense of these trends.

To begin we we can see that although men started out from a higher baseline in terms of the numbers of CIS graduates, through the first part the 1970s there was steady growth in the numbers of both male and female graduates and that this growth began to accelerate from the late 70s through to the mid 80s, albeit more rapidly for women than men. Between 1976 and 1986, when both trend lines peaked, the annual number of male CIS graduates increased by 445% while the increase in female graduates was just under 1200%. Women were catching up and catching up rapidly up until 1986 but then there was a marked downturn in interest in CIS degrees which affected both men and women but more so women. The low point in this downward phase was reached in 1993 by which point the annual number of male CIS graduates had fallen back by 36% from it’s 1986 peak but for women the corresponding fall was 52%.

From there we have a stable trend for several years and then, beginning in the mid-late 1990s, a second boom in the numbers of both male and female CIS graduates spanning the period from 1997 to 2003/2004. Again, men start from a higher baseline than women, in part due to the residual impact of the numbers of male graduates falling away less precipitously in the late 80s than was the case for women, but unlike the boom period from 1976-1986, this time it was the number of male CIS graduate that grew at a more rapid rate with a rise in the annual numbers of CIS degrees awarded to male candidates of 143% over this period compared to an increase of 124% in the number of women obtaining a first CIS degree. It doesn’t take a genius to realise, purely from the timing, that this second boom in the number of CIS graduates was associated with and driven by the late 90s “dot-com bubble” and when that bubble burst – once you allow for a lag in the data because were looking at the numbers of people graduating with CIS degrees and not the numbers starting them – so did the boom in the CIS degrees and, again, when the fall off in numbers occurred, women were hit harder than men.

In 2009, when the trend lines for both men and women bottomed out, the number of CIS degrees awarded to men was around 36% down from its 2004 peak while for women, where the number of degrees awarded peaked in 2003, the corresponding fall was, again, over 50% (56.3%) and although the pick up in numbers since 2009 has been of a similar scale for both men (24%) and women (27%) the substantially higher baseline from which men were starting out meant that there were 9,300 more male CIS graduates in 2012 compared to 2009 but only 1,800 more female CIS graduates.

So, if we are to use the trends in the numbers and proportions of male and female CIS graduates as a proxy for women “coders” – and it is by no means clear how valid that assumption is – then the questions we need to answer are:

– What happened in the mid 1980s to cause a reversal in what had previously been a rising trend in the number of both male and female CIS graduates?

– Why, when this trend reversed, did it proportionally affect women more than men? And…

– What changed over the period from the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s such that when things began to pick up again due to the nascent dot-com boom it was men, more so than women, that chose to pursue CIS degrees when, during the late 1970s and early 80s, the opposite had been the case?

Those are questions that Kenney and Henn have certainly asked but equally they are ones for which they really don’t have much in the way of convincing or compelling answers:

“There was no grand conspiracy in computer science that we uncovered,” Henn said. “No big decision by computer science programs to put a quota on women. There was no sign on a door that said, ‘Girls, keep out.’ But something strange was going on in this field.”

Kenney and Henn noted that society in the 80s could be broken into the computer haves and have-nots – and because of a targeted advertising culture, men tended to have computers. This gave men a leg-up in the classroom.

“Ads for personal computers, they were filled with boys,” Henn said.

Kenney continued, “What’s so striking about them, besides the super-cheesy 80s music, is men and boys. In this Commodore 64 ad, there’s sort of this dorky 12-year-old, sitting at this computer, and he gives this finger salute to the camera. In fact, in most of these ads, it’s just men, all men.”

“Actually there was one woman in this ad,” Henn added. “She was in a bikini and she was jumping into a pool.”

It was unclear why advertising agencies in the 80s decided that computers should be marketed toward men, but larger society picked up on the trend, with movies (Weird Science, Revenge of the Nerds, War Games), journalistic pieces and books that painted men, not women, as computer geeks.

So, yes, through the course of the 1980s, and beyond, home computers were routinely marketed as “Boy’s Toys” and this does appear to have had a marked impact on women taking CIS degrees at American universities, albeit one for which there does seem to have been a fairly straightforward solution:

Starting in 1995, UCLA Senior Researcher and author Jane Margolis conducted a study of Carnegie Mellon’s Computer Science degree path and found that half of the women in the program ended up quitting, and more than half of the women who dropped out were on the Dean’s List – they were doing well.

“If you’re in a culture that is so infused with this belief that men are just better at this, and they fit in better, a lot can shake your confidence,” Margolis said.

While growing up, women were often in a position of having to ask to play with a brother’s computer, but men never had to ask to play with a sister’s computer, Margolis found.

Margolis and the Dean of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon at the time, Allan Fisher, refined the university’s Computer Science program to be more inclusive, offering an intro course for people who never had informal coding training – those who didn’t grow up with access to a computer. Five years later, in 2000, women composed 42 percent of the program and drop-out rates between men and women were mostly equal.

Okay, so I can see how that works, although I would say that it is not an issue that is either unique to coding or necessarily tied into attitudes and values surrounding gender. Anyone entering an educational environment as a relative novice only to find themselves immediately surrounded by people who are streets ahead of them in terms of subject knowledge and experience is bound to feel rather intimidated irrespective of any pervasive cultural ideas that might be floating around to a exacerbate those feelings. That such issues appear to be tractable to something as simple as a basic catch-up course at the very least demonstrates that any cultural obstacles can be readily overcome with a bit of thought and effort.

However, even if we accept that the “Boy’s Toys” hypothesis may be a significant factor in explaining the trends we can see in the CIS degree data that still leaves open the question of why, back in the 1980s, advertising agencies very quickly seems to have decided that computers should primarily marketed toward men rather than women, no does it explain the sudden drop off in the numbers of both men and women pursuing CIS degrees from the mid 1980s onwards. There is more to this than immediately meets the eye and while the simplest and easiest answer – plain old sexism – may have a part to play here, it’s unlikely that its going to provide THE answer to those questions.

So let’s go back to the three questions I posed earlier as see if we can unearth a more c0mplete and satisfying set of answers and, of course the first question is that of why, from 1986 onwards, was there a sudden drop off in the number of people graduating from US universities with CIS degrees?

Because we’re looking at data for degrees awarded, that fall off in numbers after 1986 is a reflections of changes which took place in period between 1983 and 1987; it takes 3-4 years to complete a Bachelor’s degree in the US and so at some point in the 3-4 four years before 1987 there must have been either a decline in the number of people enrolling on CIS course or a rise in the numbers that started out on CIS course but who then chose to switch to other subjects part way through their course in order for there to have been a drop in the number of degrees awarded in 1987.

One possibility here is that we could be looking at data which reflects global changes in the US education system at that time, i.e. a fall in the overall number of people attending US universities, which could have been caused by a wide range of economic, social and demographic factors but, having looked at the overall university enrollment figures for the 1980s there seems little sign that that was actually the case. There was a small drop off in the number of men aged 18-24 who were enrolled on university degree courses during the period from 1984-87 (down by 200,000 in 1985 from a peak of just over 6 million in 1983) but not in the numbers of women enrolled at the same time, which was steadily increasing over the course of the entire decade, and the cause of even that fall in numbers appears to have been primarily demographic. Although there was a brief dip in actual numbers the trend in terms of the percentage of 18-24s enrolled on degree courses rose solidly from 40.2% in 1980 to 51.4% in 1989, which is clear evidence of an overall decline in 18-24 population being compensated for by an increase in the proportion of that population going on to higher education.

Okay, so we’re not looking for a generic economic or social cause here but something much more specific to computing as an industry or past-time and looking at when this occurred there is one very strong candidate for the cause of this sudden downturn in the numbers of people pursuing CIS degrees at US universities and that candidate looks very much like this:

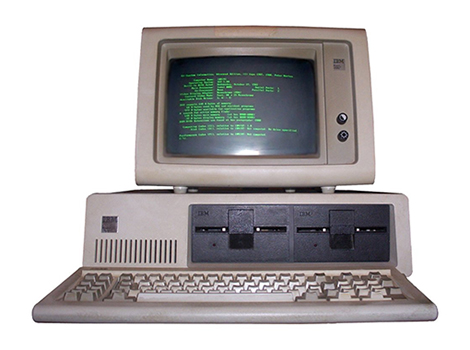

That, just in case you don’t recognise it, is an original IBM PC (model 5150) as launched in the marketplace in August 1981 and it is quite simply the biggest game-changer in the history of modern computing and information technology.

That, just in case you don’t recognise it, is an original IBM PC (model 5150) as launched in the marketplace in August 1981 and it is quite simply the biggest game-changer in the history of modern computing and information technology.

Before the PC, if you worked as a computer programmer then irrespective of whether you worked in corporate data processing, academia, the video games industry or as a developer of specialist systems in the military, industrial and technology sectors, you would have spent most of your time designing, developing and maintaining bespoke software applications, most likely using either a mainframe or mini computer such as a IBM s/360 or a DEC PDP 11 – and before you ask, the choice of photos that follows is deliberate.

The runaway success of the original IBM PC ushered in a major change in the way data processing was done in the business sector, a move over time away from large-scale batch processing using mainframes and minicomputer running bespoke software that had been designed and developed, in the main, by in-house coding teams toward real-time client-server network based systems running off-the-shelf applications, all of which resulted in a marked decline in demand for “traditional” coding skills that formed a substantial component of most degree-level CIS courses. As we moved through the 1980s and into the early 90s, what the market wanted wasn’t programmers, a field where women had maintained a significant presence stretching right back to the early days of electronic computers in the 1950s, but technicians, network administrators and hardware guys – and it was mostly guy because that side of the industry had long been an almost exclusively male preserve.

That is, I think, a key part of the story and it certainly helps to explain the sudden drop off in the popularity of CIS degrees in the mid 1980s. A university degree was your main route into the coding side of the industry but the demand for those kinds of skill was beginning to fall away as businesses moved over to desktop systems and client-server networking, creating an upswing in demand for technical skills that people either picked up on the job or though courses provided by the same companies that sold you these systems. Either way, getting job on the tech side of the industry didn’t necessarily require you to start out with a CIS degree, hence the drop off in interest in those course in the mid 80s.

Now that’s okay as far as it goes but it still doesn’t explain why, when it came to the rapidly emerging home computer market that was developing at around the same time, the advertising execs responsible for devising those early marketing campaigns came to the conclusion that computers should be regarded as “boy’s toys” and marketing almost exclusively towards men.

So how do we explain that?

Well, one theory that seems to crop up fairly often but which I think is grossly overstated and overrated tries to suggest that one of the drivers behind this early perception of computers as a male preserve stems from the fact that by far the best known and most high-profile of early “superstar” pioneers of of personal/home computer – particularly Steve Jobs and Bill Gates – were not only men but men who fit very easily into what has become, over time, the standard Geek/Nerd stereotype. That particular theory is, I do have to say, complete and utter nonsense and based entirely on people making the mistake of projecting backwards the public reputations that both Gates and Job attained only later in their business career to time when although both were reasonably well-known in tech circles, no one outside those circle had any idea who either of them were let alone that either would go on to enter popular culture and become major public figures.

Put simply, during the period we’re talking about here, which ran from roughly 1977/78 through to 1985/86, Jobs was one of the two guys who started Apple, a company which had done pretty well with the Apple II but had then completely blown out of the water when IBM made it’s entry in the personal computer market, while Gates and Microsoft were just the suppliers of the MS-DOS operating system, which you got as standard with an IBM PC. At that time, the marquee names in the tech sector weren’t people, they were corporations – IBM, Atari, Commodore, etc. – and it wasn’t really until the 1990’s that either Gates or Jobs attained their “superstar” status.

So let’s put that one to one side as being historically implausible and, indeed, entirely counterfactual because there is an explanation that provides a much better fit to the facts and it begins with the realisation that the one that the pretty much the early commercially successful home/personal computers had in common was that they were phenomenally expensive.

If you had, for example, bought an original Apple II back when it was first launched in 1977 then a complete pre-built system with just 4K of RAM would have set you back $1,298.00 while a top of the range model with 48K, suitable for use as a business computer running VisiCalc, one of the first spreadsheets and arguably the first “killer app” in terms of being a piece of software that helped to drive hardware sales, would have cost $2,638.00. The equivalent price, today, of those early Apple II computers ranges from $5,098.00 to $10,598.00 after adjusting for inflation.

So the Apple II was expensive and it’s much them same story for what were, at the time, its main rivals.

The 1977 Commodore PET 2001, the early models of which also had just 4K RAM, retailed at £795.00 for a full system which included a 9-inch monochrome monitor and a built-in cassette deck for storage, while the Tandy/Radio Shack TRS-80, which also went on sale in 1977,was priced at $599.99 for a basic 4K RAM model, again with a 12-inch monochrome monitor and external cassette deck for storage, although for an extra £290.00 you could have the 16K RAM model opening up the option of replacing the cassette deck with a mini disk, just so long you were happy to cough up another $398.00 for an expansion interface and an upgraded version of BASIC and then a further $499.00 for the actual disk drive.

Okay, so things did get a little bit cheaper in October 1979 when Atari started shipping its first 8-bit home computer, the Atari 400, with 8K RAM, no monitor (although it had a TV output) and a cartridge slot for software, including games, at a price of $549.00 – somewhere in the loft I actually have an old 8-bit Atari (a later 800XL model with 64K RAM) which I bought secondhand in the late 80s for £40 just so I could play the original Star Raiders cartridge – but that’s still very expensive for a computer that was being pitched more to the home market than the Apple II, PET or TRS-80, which were seen more as business-orientated systems.

Okay, so thinking about this purely from a marketing perspective what we have here are some new, innovative and very expensive pieces of kit to sell for which we need a target demographic that is not only likely to be interested in new technological gadgets but which also has sufficient disposal income to be able to afford to lay out anything from $600 to $3,000 on what could well be a hobby purchase, and given that we are looking here at conditions in the late 1970s it should be pretty obvious that one of the largest, if not the largest potential target demographic for these products would have been white, middle-class, professional men, the kind of people who, at the time, the most likely to have either sufficient disposal income to pursue a new and relatively expensive hobby and/or also the most likely people to be in the kind of position where they could write-off the cost of purchasing one of these new computers as a legitimate business expense.

So that is one very good reason which would explain why advertisers set about pitching these early home computers as “boy’s toys” but it’s not the only reason because if, at the time, you weren’t in a position to be able to pay top dollar for a new computer that worked straight out of the box there was another alternative entry point to this particular hobby, one which came in at a lower initial outlay, and that entry point would have looked something like this:

Okay, so what you are looking at there is an old British home computer, the Acorn Atom, which dates from around 1980-1982, or rather what you are looking at is the kit that you could buy in 1980 from which you could build your own Atom for anything between half and two-thirds of the cost of a factory-built model. A fully assembled Acorn Atom, the base model of which came with just 2K RAM, would have set you back around £170 when it was first launched in 1980 while a fully expanded model with 12K RAM and a floating point ROM” (don’t worry if you don’t know what that means, it’s not important) would have set you back over £200, while the launch price for the Atom in kit form was around £120.

So if – during the late 70s and very early 80s – you were interested in these new home computers and wanted to get in on the ground but you weren’t the kind of white male middle-class professional who could afford a complete factory-built system then your only alternative, if you wanted to keep the cost down, was to buy your computer as a kit and assemble it yourself. But of course what that also means is that if you’re in the business of selling kits full of assorted microchips, circuit boards and resistors that people have to assemble themselves and not just fully-assembled computers then on that side of your business you are aiming your product(s) at a very specific pre-existing market of electronics hobbyists, radio hams and the like; the kind of people you’d typically see on a wet Saturday morning rooting around in the components bins in your local Tandy/Radio Shack looking for a 10 Ohm resistor, the vast majority of whom would have also been men.

What seems to have been forgotten over the last 30 years or so, as people’s notions of what constitutes “technology” have increasing come to dominated by thoughts of computers and the Internet, is that the original technology geeks weren’t computer programmers, they were radio hams, radio-controlled model enthusiasts and electronics hobbyists – hardware guys, again – and for all that women were a major presence in the early days of computing on the programming side of the industry, the hardware side of things remained heavily dominated by men throughout that period.

There, I suspect, we have a key component of our explanation as to why, only a matter of 2-3 years after the period I’ve been describing, the world of advertising had firmly settled on the idea that computers and everything associated with them should be regarded as a solidly male preserve even though, by that point, the actual computers they were selling had passed beyond the point of being solely of interest to middle-class businessmen and nerdy hobbyists and has fully entered the realm of mainstream consumer electronics. Okay, so I’m not going to rule out the possibility, if not likelihood, that sexism also played a part in locking down the idea that computers were almost exclusive a male preserve but any such assumptions on the part of either the technology companies of the time or the people and businesses that devised their advertising would certainly have been heavily reinforced by those first few years of the personal computer market when a combination of the high cost of a fully assembled system and the pre-existing male-dominated culture surrounding hobby electronics more or less guaranteed that most of the early adopters would have been men.

So, sadly, at that point the die was cast and computing (and computer programming) became, at least so far as popular culture was concerned, a career for the boys, even though that certainly hadn’t been the case on the coding side up to that point in time.

That this all took place at the same time as major shift in the technological underpinnings of business computing, brought on by the widely successful entry of IBM into the personal computer and business desktop markets, undermined the one area in which women had made serious inroads, is doubly unfortunate not to mention a serious setback from which women coders are only very recently beginning to recover in any significant numbers and only then at the cost of serious opposition (and harassment) from the male-dominated culture that was permitted to grow, unchecked, into the space vacated by women coders in the mid 1980s.

There could, admittedly, be other factors that played their part in this rather sorry story. There are certainly one or two comments under Conditt’s article which suggest that part of the cause of the mid 80s fall in CIS degrees could lie, at least in part, in the 1983 North American video games crash. That’s a potentially interesting line of inquiry but I’m far from convinced that the games sector, at that time, was big enough to generate the effect we can see in the degree awards data over such sustained period.

There is also – predictably – quite a bit of “what about the MENZ” crap in those comments, the less said about which the better except, perhaps, for noting that, as usual, most of it seems to be coming from people for whom even the simplest possible explanation of any particular phenomenon would serve to stretch their limited intellectual capacities well beyond breaking point. There is nothing much wrong with either Conditt’s article or the work put in by Kenney and Henn save for the fact that I suspect none of them are old enough to have been around at the time and as such they don’t have benefit of having first hand knowledge and experience of that period to guide them in their efforts to make sense of the data.

One other alternative to consider: the discrediting of the feminist movement. Note that in the 60’s and 70’s you had the sense among (many) women that they had the need and duty to break boundaries, to go into fields and places where they had previously been excluded- in much the same way that the civil rights movement had to do the same (think: lunch counters). With the defeat of the ERA and the rise of Reagan and the conservatives, women (really, everyone) lost the cultural imperative. Feminists stopped being human rights crusaders, and instead became “feminazis”, evil harridans that no one, not even women, wanted to be associated with.

The reason they didn’t advertise to Women is because they knew they couldn’t sell to to women. I’m sure, if there was any way they could’ve sold computer to Women, they would have done it. I think, the reason there aren’t more women coders is simple: They don’t like it. Just like Men don’t like barbies. Plain and Simple.

Oh boy. So, on the one hand, you have this deep, wide ranging analysis, and then you have Gerald coming along telling us “‘girls like barbies; boys like computers – simples!”

If what you were saying contained a shred of truth, there would be no such thing as an ‘untapped market’, because marketing teams in the 70s and 80s, in all their perfect wisdom, would already have got everything right. Poor advertising can do worse than cause no positive impact – it can destroy demand by excluding a demographic.

This isn’t true. Boys do like Barbies, they just don’t know it. Both boys and girls like creative play where they act out stories. This is an important part of childhood development. The difference is that toy companies dress up this creative play in pink for girls and guns for boys. Instead of dolls they are called action figures. But the underlying creative need is the same.

This is so true. My son is somewhat language delayed and we took him to a therapist. At the therapist, she took out dolls and had the dolls put another doll to bed, act out various scenarios, etc, as a way to encourage language development.

Then I realised; we had nothing resembling a humanoid object in our house for our son to play with. All we had were cars, cars, cars. I was depriving my son of developmentally appropriate toys because I didn’t think a boy would play with doll… which of course he did!

I do believe there are natural differences in toy preference in small children. The problem is that we *overspecialise*- we see that a boy has a slight preference for cars and then buy 5 billion cars. We see that a girl spends a little longer with a doll and invest in a expensive doll house with all the trimmings. And even worse, when we see children playing with “opposite gender” toys, discourage that.

I see this over and over in play groups. Just two weeks ago I saw a 2.5 year old girl trying to play with a toy workbench. Her mother told her, “don’t play with that, that’s a boy’s toy.” Twice. The girl gave up and went to play with the kitchen set.

The problem is that parents are unable to see that gender preferences can both exist, AND that it is bad to go overboard with gender preference and even WORSE to limit your child by actively preventing them from playing with opposite gender toys.

“the male-dominated culture that was permitted to grow, unchecked, into the space vacated by women coders in the mid 1980s”

You make it sound like male culture is a roach infestation or something. What’s wrong with men liking something and building an industry around it?

There’s a lot of interesting data and analysis by the author, but her mean-spirited underlying ideology ruins the post for me.

What’s wrong with it is the industry will be insular and not achieving it’s full potential.

Yes, how will computing ever grow from a tiny niche into a mighty economic engine without the even contribution of ovaried programmers? Surely you can’t expect to write revolutionary operating systems and web platforms with 80+% males.

We had better destroy the organic culture of computing groups and replace it with bland inoffensive corporatism/feminism to lure in women or computing will never get anywhere

The scary thing is, I think your serious.

What are you, a GamerGator?

Nice work, McCarthy.

One thing to note about this shift is that mainframe programers very often worked in high-level languages such as COBOL, while PC programmers in the early 1980s would have mostly been bit-banging hardware in assembly language. Also, Unix/C/C++ culture was on the rise in the 1980s, and it always seemed to have a certain aspect of egos and elitism.

I also think the pictures selected by the author allude to the cultural shift that went on. Rather than a team of people working in a data processing room, the predominant image of the PC programmer is the lone genius hacker pounding out inscrutable code in a darkened room.

So, perhaps in the 1980s, CS was seen as a more difficult (and less fun) degree to succeed in than it was in the past.

I also believe the video game crash did have an effect, not because games were very economically important, but because video games and home computing was a huge popular culture fad. When the fad died, so did a lot of the mainstream media coverage of the computer industry.

In regards to women and mainframes, that trend actually goes back a lot further than people think. The original “programmers” on the Eniac project (1940’s, the first electronic computer in the U.S.) were *all* women. Programming, at that time, was viewed as a relatively menial task, not to be done by the white coats. The gender association reflected the biases of the time. But whatever the origins, it provided entree to women into a field that turned out to be important.

In the 1960s and 1970s, IBM ran a very active mentoring and promotion program for women that brought many of them into the field. Offhand, I can’t think of a female C-level executive in our field prior to Marissa Meyers who *wasn’t* trained and mentored at IBM. AT&T did not have a comparable mentoring process, so it never became part of the sociology around UNIX. Neither did DEC. As energy shifted from mainframes to personal computers. it wasn’t just the cost of the *machines* that fell; it was the cost people were wiling to invest in training and mentoring. Relative upstarts like Compaq or Dell in their early stages had no capacity for mentoring *anyone*, and certainly not for mentoring women, who often needed to transition from other fields and/or other backgrounds. Microsoft still suffers from a “boy’s club” mentality even today. And that sets tone for a lot of others.

I find these 2 articles a good example of the difficulties in drawing conclusion from data. As a graduate in the mid-70’s, I would like to offer two observations.

1. I was admitted to San Jose State University about 1974 to Engineering. One year later, I was allowed to change to a NEW degree program in Computer Software and Information Systems. Most schools had Math degrees back in the ’40’s, but I think the education system was slow to offer Computer Science degree programs.

2. When I began working at HP in 1976, several of my male co-workers got started in computers while working in the military. (I used to recommend a military option to women– that was the place to go for cutting edge work in data communications. Remember, the internet was spawned there.) I never knew anyone to take this advice:-)

I don’t see why any of this is such a big deal. There are no real barriers to entry of women into the field of information technology or software development. In fact, in the USA at any rate, there are significantly more women earning college degrees than there are men earning degrees. So, it certainly is not due to lack of opportunity for women. All this wringing of hands as to why there aren’t more women in IT seems to me to be nothing more than a manufactured crisis by the grievance industry.

Look at the economy. It appears that your peaks for women in computer science occur after an economic downturn, and once the economy becomes pleasant again, the number of women goes down. What that tends to indicate is that the peaks are caused by women seeing computer science as a field that is secure and relatively lucrative, but not their preferred field. The same peaks happen for men as well, indicating that there’s a certain number of men for which the same applies. I was at university during that early 1980’s peak and can attest that a large number of men *and* women entered the field at that time not because they had any preference for computers, but, rather, because they felt it was a secure and well paying field. What stands out in the graph however is what happens with males from 1998 onwards. The numbers grow very fast while women only return to their previous peak. I have no explanation for that.

Regarding personal computers in the 1980’s: They were primarily being bought by business departments inside corporations to replace word processors and typewriters. They weren’t networked. IT had banned personal computers and thus they were bought out of the general office equipment budget of individual departments, the budget that otherwise would have gone to purchase word processors and typewriters. And the executives who controlled those budgets were primarily men. Thus why the marketing of the IBM PC and its clones was at men — men controlled the office equipment budget. The users of these computers inside Fortune 500 companies, however, were predominantly women — they replaced typewriters on secretaries’ desks. Most executives did not actually have a personal computer within their office proper, it was outside on the secretary’s desk. This was because the vast majority of executives did not know how to type and had no desire to type — typing was women’s work, they felt.

I have no such explanation, however, for why home computers of the time such as the BBC and the Commodore 64 were primarily marketed to boys. It may be because the people who created these computers were hardware geeks and thus only knew how to market them to other hardware geeks. Or it may have been that because they were so primitive that you had to actually manipulate hardware registers to make them do anything interesting (even in BASIC you ended up PEEK’ing and POKE’ing hardware registers a lot to do things like, e.g., program sprite graphics for simple games), thus it simply wasn’t viewed by the (male) advertising executives as something that girls would be interested in.

And yes, I was around in those years. I was writing applications for microcomputers in the late 1980’s that would have been written for industrial minicomputers in the late 1970’s. All that happened was that the hardware had gotten smaller and cheaper — the fundamental job of a software programmer had not changed. I didn’t get my first computer network gig until 1990 — BNC connectors on coax, yay. There just were not a lot of PC hardware jobs out there other than as repair technicians during the 1980’s. Network engineers didn’t happen until around 1990, and operations engineers really didn’t take off as a job until the Internet started taking off in 1995. Neither seems to have impacted the number of women entering the field, it held fairly steady during those transitions. So I think that hypothesis can be discarded… but I have no new one to replace it.