If you’re in any doubt at all as what top-notch science blogging looks like then let me direct your attention to three new articles by Orac, Steven Novella and David Gorski, all of which tackle a new paper, published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, under the rather prosaic title ‘Active Albuterol or Placebo, Sham Acupuncture, or No Intervention in Asthma‘.

As titles go this one is very much a matter of ‘does what it says on the tin’. The study, by Michael E Wechsler et al., compares the performance of a standard asthma treatment, Albuterol (aka Salbutamol in the UK), against that of a placebo (a sham inhaler) and sham acupuncture in a group of patients with mild to moderate asthma, with a ‘no intervention’ group as a control, and the result of the study are very much as you’d expect. When patients were asked to provide a subjective assessment of how they felt after using the treatment modality assigned to them – and this a double-blind study in which neither the participants nor the researchers would be aware of exactly which patients were receiving which treatment option, save for the ‘no intervention’ control group – the study generated the following results:

So, participants were asked to rate the improvement in their symptom on a ten-point scale which ran from 0 (no improvement) to 10 (complete improvement) and, as the graph indicates, all three test interventions performed considerably better than the no intervention control group, with Albuterol – a bona fide asthma medication – performing a little better than either placebo or sham acupuncture, both of which were more or less on par with each other in terms of subjective effect.

So far, there’s nothing particular surprising about the results of this study but there is a rather interesting back story here which merit a little attention.

This is primarily a CAM (Complementary and Alternative Medicine) study and, over the last few year, something like $2.5 billion in Federal tax dollars has been ploughed into scientific studies of so-called CAM ‘therapies’ by a US government agency called the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) with, to say the least, rather underwhelming results. NCCAM has failed, miserably, to validate any of the main CAM ‘treatment’ modalities. In fact, in terms of concrete achievements, NCCAM’s most notable successes have been limited to uncovering evidence that a few common herbal ‘remedies’ are completely ineffective with the result that sales of those remedies have fallen in the US.

By way of a response to NCCAM’s failure to deliver any credible scientific evidence to support the use of CAM ‘therapies’ and ‘treatments’, some US-based CAM advocate have started to latch on to the evidence that acupuncture, homeopathy and the like perform no better than placebo by arguing that placebo medicine, itself, has a valid place in contemporary medical practice. The circular nature of this argument should be obvious. If we buy into the idea that placebos are, in themselves, a powerful or effective treatment for many common ailments then it follows, somewhat logically, that CAM modalities like homeopathy also have a valid role to play in modern medicine as these are, in the eyes of their supporters, perfectly respectable and effective ways of administering a placebo.

Naturally, I don’t buy this line of argument at all. Even if we accept the proposition that there are valid uses for placebo medicine, it doesn’t follow automatically that we’re justified in using CAM modalities as placebos. Using placebos inevitably entails the introduction of a degree of deception into the doctor-patient relationship, which is best avoided for ethical reasons unless it can be shown that the use of placebo will result in a measureable benefit to the patient which significantly outweighs the ethical ‘cost’ of deceiving thw patient as to the nature of the treatment they’ve received. Using homeopathy or acupuncture as a placebo takes that deception to unacceptable levels by actively fostering unscientific and irrational beliefs in the patient in order to generate the placebo effect. It’s one thing to decieve a patient by giving them a sham anti-depressant or analgesic, leaving them still with the belief that the real thing – and, therefore, real, scientifically tested and validated medicines, actually works. It’s quite another to fill a patient’s head with unscientific bullshit and pseudoscience to the extent that they come to believe, incorrectly, that quack remedies and therapies that have no basis whatsoever in science might work, not least as there is an omnipresent risk that, by fostering such a belief while treating a patient for a minor, self-limiting ailment, one may easily induce the same patient to rely on CAM modalities should they contract or develop a much more serious condition.

What has drawn the attention of three of the very best science bloggers you’ll anywhere on the internet to this particular paper is, first and foremost, the fact that its authors have attempted to spin the results of the study into an argument which ostensibly support the use of placebo medicine, which might have been all well and got had the study, in common with a sizeable quantity of other published research in this area, stuck firmly to the use of self-reported subjective measures of apparent improvement in patient symptoms. CAM researchers and advocates are, by and large, more than happy to knock out studies which measure the apparent efficacy of CAM modalities in purely subjective terms by asking patients whether they felt any better after using the particular treatment that the study was aiming to evaluate – and they’re even happier to do this if they think they get away with carrying out such studies without adequate controls, full blinding or randomisation or as adjunct studies in which their quack remedies are evaluated only in conjunction with other, scientifically validated, treatments.

Why? Because deep down, and even if they won’t openly admit it, they know that no matter how useless their quackery might be, as long as its not positively harmful, it will likely generate some sort of positive-looking effect that can be passed off of ‘evidence’ of efficacy, merely because it acts as a placebo.

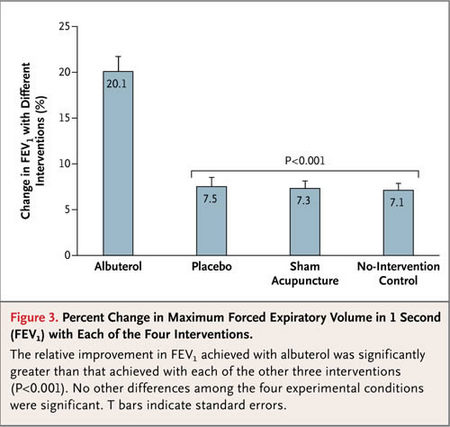

What, however, makes this study even more interesting is the fact that its authors did not just confined themselves to taking subjective measurements of the apparent improvement in symptoms experienced by patients for each of the modalities under test, they also included an objective test in the design of the study, specifically a test of lung function – more or less the old ‘take a deep breath and blow it out as hard as you can’ test you’ll see wherever your local PCT has got a smoking cessation promotion on the go.

This part of the study generated the following, extremely interesting, results:

So, although the patients receiving placebos may have felt better, in reality neither of the two placebos had any real impact at all. Both performed only marginally better than than the no intervention control and the differences are small enough to call that a no effect result, which the scientifically validated treatment, Albuterol, generated an improvement in respiratory function some three times better than both the trial groups and the control. in short, the placebo arms of the study had no measurable impact on the patients’ physical well-being, they just made the patients who received those intervention feel a little better about being somewhat breathless. And if you take a good close look at the articles by Orac and David Gorski, you’ll also find an additional set of results graphs which show that of the four group, only the Albuterol group showed any consistent improvement in lung function during the study, while both placebo arms and the no intervention group were, to say the least, extremely hit and miss – and mostly miss.

As I’ve already noted, all three articles go on from discussing the actual results of the trial to criticise the manner in which the paper’s authors’ have tried to spin their results as supporting the increased used of placebo medicine, and to be perfectly honest I’ve nothing much to add to those critiques that hasn’t already been covered in greater depth and clarity than could probably manage.

What does intrigue me, however, is the question of what this study might have to say about how the placebo effect actually works.

This is a question that Steven Novella directly addresses with the following observations:

Despite the spin of the authors – these results put placebo medicine into crystal clear perspective, and I think they are generalizable and consistent with other placebo studies. For objective physiological outcomes, there is no significant placebo effect. Placebos are no better than no treatment at all.

It is worth noting that there was still an improvement over baseline, just as there was in the no treatment group. This likely reflects non-specific effects and statistical effects, like regression to the mean. There are many potential effects lumped into the “the” placebo effect that gets measured in the placebo arm of a clinical trial. By comparing to the no treatment group what this study shows is that, for objective outcomes, the placebo effect is entirely made of these non-specific and statistical effects.

This further means that there is no expectation effect or mind-over-matter effect that has a measuring objective physiological effect.

For subjective outcomes (the patient reporting that they feel better) there is a large additional effect. This is likely comprised of reporter bias, expectation, and other psychological effects (which add to the non-specific and statistical effects mentioned above).

What this study strongly suggests is that placebo effects, however, are not real physiological effects worthy of pursuit. They are largely, if not entirely, non-specific therapeutic effect and statistical illusions.

For myself, I’m not quite so confident that we can write off the possibility of real physiological effects that may be worthy of pursuit as my suspicion is, in this case, that the subjective ‘improvements’ reported by the placebo arms in this study may traceable back to non-specific therapeutic effects that are, at least in part, also physiological effects.

We are dealing here, of course, with asthma and this is a condition with which I’m pretty familiar as its one that my brother has suffered with since he was a very small child – he actually had a pretty rough time of thing all around as he contracted pertussis (whooping cough) when he was only nine months old, and developed asthma more or less directly afterwards. The striking thing about asthma, of course, is that it affects respiratory function and leaves sufferers feeling breathless and, when an attack kicks in in earnest, quite literally fighting to catch their breath – and when that happens it triggers a very basic physiological mechanism, the acute stress response, which is commonly referred to as the ‘fight or flight response/reflex’. In short, if we unexpectedly find ourselves in a situation in which we cannot breathe properly then we start to panic and our body responds automatically by giving us a big old shot of adrenaline which, amongst other things, causes our heart rate and lung action to accelerate. For someone with asthma is a far from ideal physiological response as, in a severe attack, they will quickly begin to hyperventilate which only makes their situation even worse.

In this study, we’re dealing only with patients with mild to moderate asthma who were, therefore, unlikely to undergo a severe and potentially life-threatening attack of the kind that would cause an acute stress response to kick in in earnest but, on beginning to feel breatheless these patients would, nevertheless, experience a degree of anxiety sufficient to trigger a stress response with its concomitent adrenaline ‘rush’ and other physiological effects. It seems reasonable to surmise, therefore, that at least part of the reason that patients in the placebo arms of the study reported feeling better after using the placebo may stem from a reduction in feelings of anxiety and, therefore, a lessening of the physiological stress response, generated merely by the act of undergoing some sort of treatment for their condition.

This is, of course, a non-specific therapeutic effect but, perhaps a significant one in so far as it provides a hypothesis that can be readily generalised to other conditions and to a wide range of other treatments and therapies, including therapeutic contact with a medical practitioner. Its pretty well documented that the mere fact of seeing a doctor, when we’re feeling unwell, will make us feel at least a little better even if the only treatment we’re given is a bit of solicitous concern and a reassurance that whatever is ailing us is nothing much to worry about and will likely clear up of its own accord in a day or two. This is also far from being a novel or surprising observation insofar as its generally accepted that a reduction in anxiety and stress is, at least, a secondary effect of therapeutic contact with a medical practitioner and that this may, in turn, help alleviate some symptoms, where these are known/thought to be stress related. However, as asthma is a condition which is particularly sensitivity to the physiological effects of stress, it may be the case that the alleviation of stress and anxiety by means of a placebo may be far more important in explaining the findings of this study than the term ‘secondary effect’ might otherwise suggest.

This, in turn, raises the question of whether, and to what extent, we may be undervaluing the importance of stress/anxiety reduction as a component of the placebo effect, or perhaps placebo effects, as it may well be the case that what we call ‘the’ placebo effect is in fact, and like autistic spectrum disorder, not a singular effect but rather a complex class of causal effects which, nevertheless, generate similar-looking outcomes.

It also, perhaps, ties this study very neatly into the established modus operandi of CAM practitioners, quacks and of the ‘wellness industry’ in general, a sector which both feeds off and contributes to the creation of a pervasive information landscape in which we’re all drip-fed a near constant stream of messages design to heighten anxieties about our own health and general well-being. It is, today, almost impossible to pick up a newspaper or magazine without running across an article or advertisement telling us that we may be at risk of developing one debilitating condition or another, or that some seemingly mundane foodstuff is either a potential cause of or cure for a particular unpleasant disease and, no matter the issue, there are always plenty of quacks waiting in the wings to sell us just what we (mistakenly) come to think we might need to quell our artificially induced anxieties.

In recent times, the loose community of science bloggers and skeptics have done a pretty good job of documenting and debunking quackery but, I strongly suspect, in taking on the homeopaths and snake oil peddlers, we are ultimately dealing only with the symptoms of a disease and not the cause.

Thanks for another very useful piece.

One quibble: unless I am very much mistaken, David Gorski who is a co-editor and contributor at Science-Based Medicine is also “Orac” of Repectful Insolence (and makes no pretence of being two people). Both blogs are excellent, rigorously factual, overlap in subject matter, but vary in style. You might even say they were complementary!

The interesting question that comes out of this for me is: If a patient is stubbornly insisting on being given homoeopathic treatment is it unethical to give them a glass of water?