I have long had a particular interest in the field of “zombie statistics”, statistics that are widely circulated as factual information but which have become entirely detached from their original source to the extent that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to establish their validity. Some zombie statistics may be complete fabrications or no more than the product of now forgotten piece of PR-reviewed research*. Others started out as genuine statistics but are, by now, so divorced from their original time and context as to be essentially meaningless.

*Research generated by Public Relations companies for marketing purposes using biased methods which, naturally, place their clients in the most favourable possible light.

A favourite example, and one that is still doing the rounds, is the claim that adolescents aged 12-17 are the largest consumers of online pornography. You can see a contemporary example of this particular claim at an organisation calling itself ‘Safety Net’ which advocates for a mandatory opt-out system of online porn blocking.

The single largest group of internet pornography consumers is children aged 12-17 (Psychologies Magazine).

The given source for this ‘statistics’ – although not named explicitly – is a 2010 article by Decca Aitkenhead which is, itself, but a single step in a chain leading back to the earliest known version of this particular statistic, in which is it presented as follows:

The most frequent exposure to pornography is reported by adolescents between twelve to seventeen, a finding reported by the Canadian as well as the 1970 Commission survey. While sexual knowledge appears to be acquired at younger ages, it remains unclear what role pornography plays in this “sex education” process.

That statement is taken from Chapter 3 of Part 4 of the Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography: Final Report, more commonly known as The Meese Report, which was published in July 1986, which means it predates the publication of the first ever web page by six years. If that we not enough, one of the two sources it gives is a survey carried out for the 1970 report of the President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, which was set up by US President Lyndon B Johnson and which published its final report during Nixon’s first Presidential term – the other, Canadian, survey dates to 1985.

This particular zombie statistic is now just over 50 years old and predates the inception of the World Wide Web by 22 years. At the time this particular statistic first emerged in the United States, the two major, readily accessible, adult magazines of the period, Playboy and Penthouse, were pushing the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable by publishing pictorials that hinted at the existence of pubic hair with Penthouse being the first to fully cross the Pubicon into full frontal nudity around autumn of 1970, a move Playboy would not make until the publication of its January 1972 issue featuring Marilyn Cole.

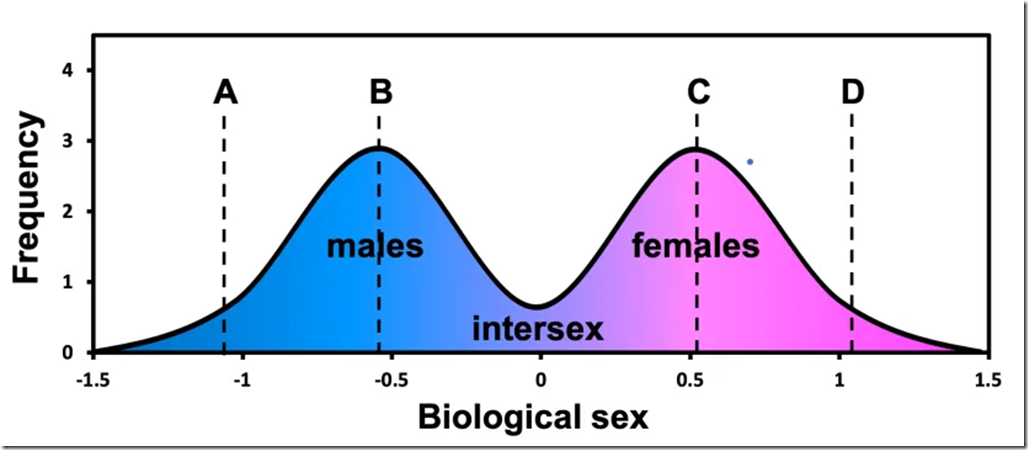

Anyway, enough about past adventures in the realm of zombie statistics and on to the subject of this article which is not a zombie statistic but a zombie graph, one which purports to depict the existence of biological sex as bimodal spectrum ranging from male through ‘intersex’ to female. The graph is frequently posted on Twitter by trans-activists and their self-styled allies in support of their contention that biological sex is not binary and exist as a spectrum and it generally looks something like this, albeit that many versions of this graph are posted without labels identifying what is being measured on each of the two axes:

In this particular version, the label for the X axis reads ‘Biological Sex’ which raises one very obvious question, if you understand statistics.

How – exactly – is biological sex being quantified and measured in order to create this distribution?

What we appear to have here is some sort of constructed scale ranging from – perhaps – hypermasculinity to hyperfemininity at the further ends of the distribution but no clear idea of the actual basis for this hypothetical scale and, consequently, no means of evaluating it against real world observations and real world data in order to assess its validity (or otherwise).

Luckily, the original version of this graph can be traced back to a scientific paper published in the American Journal of Human Biology in 2000.

“How Sexually Dimorphic Are We? Review and Synthesis” by Blackless et al (2000) is a review of extant literature on the incidence of “Differences in Sex Development” (DSDs) or “Intersex” conditions as they were commonly referred to at the time, and the bulk of the paper’s content deals with the business of deriving estimates for the overall incidence of a number of different DSDs.

This particular paper is notable as being ‘Ground Zero’ not only for the ‘sex spectrum’ graph but also for the claim, popularised by Anne Fausto-Sterling’s book “Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality”, that the prevalence of DSDs might be as high as 1.7% of the population – the paper may have been published in the same year as the book, but was originally submitted for publication in 1997 and Fausto-Sterling is listed both a co-author on the paper and the paper’s corresponding author.

A comprehensive critique of the paper and its claims about the overall prevalence of DSDs is beyond the scope of this article but more than adequately covered the contents of a 2002 paper by Leonard Sax, “How common is intersex? A response to Anne Fausto-Sterling” from the Journal of Sex Research, a full PDF of which can be acquired from this link. If you’re not up for reading the entire paper, Sax’s abstract sums things up pretty nicely:

Anne Fausto-Sterling’s suggestion that the prevalence of intersex might be as high as 1.7% has attracted wide attention in both the scholarly press and the popular media. Many reviewers are not aware that this figure includes conditions which most clinicians do not recognize as intersex, such as Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome, and late-onset adrenal hyperplasia. If the term intersex is to retain any meaning, the term should be restricted to those conditions in which chromosomal sex is inconsistent with phenotypic sex, or in which the phenotype is not classifiable as either male or female. Applying this more precise definition, the true prevalence of intersex is seen to be about 0.018%, almost 100 times lower than Fausto-Sterling’s estimate of 1.7%.

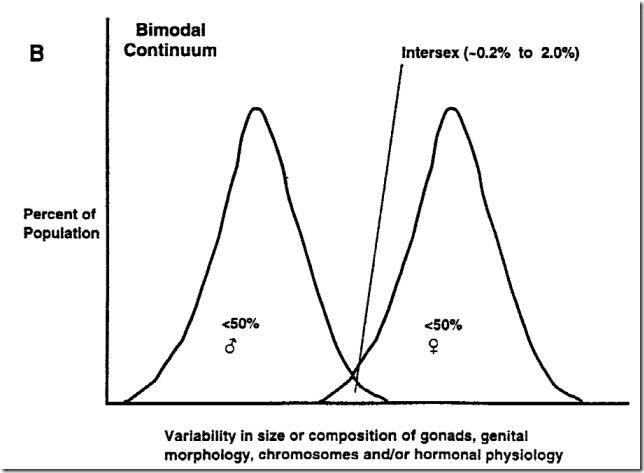

Getting back on topic, we still have the unanswered question of exactly how biological sex is being measured and quantified to produce the bimodal distribution in the ‘sex spectrum’ graph. the answer to which lies in this graphic from Blackless’s paper:

So what we have here is a model population distribution in which the x-axis consists of some sort of composite variable measuring on “Variability in size or composition of gonads, genital morphology, chromosomes and/or hormonal physiology” and to go with the graph we have this body of text:

Our culture acknowledges the wide variety of body shapes and sizes characteristic of males and females. Most sexual dimorphisms involve quantitative traits, such as height, build, and voice timbre, for which considerable overlap exists between males and females. Many cultures use dress code, hairstyle, and cultural conventions, e.g., the view that in couples the male should be taller than the female, to accentuate awareness of such difference (see Unger and Crawford, 1992). But most consider that at the level of chromosomes, hormones, and genitals, dimorphism is absolute and, by implication, such traits are discrete rather than quantitative. Clearly, as a generalization, such a viewpoint makes some sense. However, developmental biology suggests that a belief in absolute sexual dimorphism is wrong. Instead, two overlapping bell-shaped curves can be used to conceptualize sexual variation across the population (Fig.1). Within each major bell, genital morphology varies quantitatively, as shown, for example, by Fichtner et al.(1995). In the region of overlap, qualitative variation in chromosomal and genital morphology and in hormonal activity exists. If the view of the human population schematically illustrated in Figure 1B is accepted, the requirement for medical intervention in cases of intersexuality needs to be carefully re-examined. It seems likely that changing cultural norms concerning sex roles and gender-related behaviors may encourage a willingness to engage in such a re-examination

I’ve omitted figure 1A which depicts two non overlapping bell curves labelled male and female as an illustration of absolute dimorphism.

The most obvious problem here is the lack of clarity over the nature of the variable on the graph’s x-axis. The labelling on the graph suggest a composite variable derived from measurements of variations in four factors – gonads, genital morphology, chromosome and hormonal physiology – but also contains a couple of problematic conditionals – ‘size or composition’ and ‘and/or hormonal physiology’ – suggesting a variable whose definition and composition changes at different points in the distribution. Meanwhile, the accompanying text identifies variations in genital morphology as a quantitative variable in the regions outside the area where the two bell-curves overlap while suggesting that within that region it magically changes into a measure of qualitative variation alongside other qualitative measures of variations in chromosomal morphology and hormonal activity which are said to exist only within this region.

So what, exactly, is the variable on the x-axis of this graph?

The answer seems to be that it is whatever the author wants it to be in order to conceptualise sexual variation across a population using this graph regardless of its actual validity as a measurement of any description, let alone as a measure of sexual variation across a population. The vast bulk of the distribution appears to be premised solely on variations in genital morphology, literally defining ‘maleness’ in terms of things like penis size and ‘femaleness’ in terms of…

…who knows for sure?

Only within the supposed ‘intersex’ region, do other factors come into play and then only – apparently – as qualitative measures of maleness and femaleness.

Whatever this graph is meant to represent, the one thing it categorically doesn’t depict is variations in biological sex.

Working from the paper’s proposed definition of ‘intersex’ to the model depicted by the graph there is also a glaring omission, not that this is made clear anywhere in the paper.

Of the four characteristics listed in the x-axis label, only one can readily be used to generate bimodal population distributions using real world data, this being ‘hormonal physiology’ and not genital morphology – variations in genital morphology could be measured, in principle, but to do so one would have establish some sort of baseline for measurement based on population averages (or maybe a Platonic Ideal) and decide exactly how you’re going to express your measurements of variability as a single variable, so there is lot of extra work involved compared to testing for hormone levels using established methods on an established scale.

Both males and female naturally produce sex hormones, specifically testosterone and the two oestrogens (estrone and estradiol), within standard ranges for each sex and some DSDs do affect the endocrine system in ways which lead to variations in hormone levels which take individuals outside the normal range for their biological sex and into the range of the opposite sex. So why have the authors not incorporated variations in hormone levels into the graph as a quantitative measurement?

The short answer is that it breaks the model upon which the graph is based.

The normal adult male range of serum testosterone levels is around 300-950 nanograms per decilitre (ng/dl) while for women its around 8-60 ng/dl, so on the face of it there is no overlap in these distributions. However, the gap between the two distributions can be bridged by a number of clinical conditions which result in hyperandrogenism in females, the major cause of which is Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) which accounts for 70% of all such cases. PCOS is a common condition affecting 6-12% of women and, were it included in this model within the scope of a quantitative measure of hormone activity, would swamp the data from DSDs leading to an ‘intersex’ region on the graph in which the majority of people were women with PCOS.

The distribution for the oestrogens are equally problematic for a different reason. The normal adult male range is 10-60 picograms per millilitre (pg/ml) for estrone and 10-40 pg/ml for estradiol while for premenopausal adult females the normal range is 17-200 pg/ml for estrone and 15-350 pg/ml for estradiol. In both cases, not only is there an overlap between the male and female distributions for both hormones but the extent of the overlap is such that a majority of males with perfectly normal levels of oestrogens will fall within the lower end of the normal female range.

And, again, we break the model on which the graph is based because we have an overlapping region between distributions in which the vast majority of individuals are males and females with oestrogen levels with the normal range for their biological sex and not one consisting of individuals with DSDs.

Within the paper, the authors claim to define ‘intersex’ as follows:

We define the intersexual as an individual who deviates from the Platonic ideal of physical dimorphism at the chromosomal, genital, gonadal, or hormonal levels.

Such as definition, when applied to hormone levels, would classify many women with PCOS as ‘intersexual’ on the basis of their elevated testosterone levels and many normal males and females in the same way due to their otherwise perfectly normal levels of estrone and estradiol, demonstrating not only that this premise is fundamentally flawed but also that the authors must have been aware of this flaw hence the omission of hormonal variations as a quantitative variable when constructing their bimodal graph.

This is not the only fundamental flaw in this premise, as Sax notes in his response paper:

Using her [Fausto-Sterling] definition of intersex as “any deviation from the Platonic ideal” (Blackless et al., 2000, p. 161), she lists all the following conditions as intersex, and she provides the following estimates of incidence for each condition (number of births per 100 live births): (a) late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia (LOCAH), 1.5/100; (b) Klinefelter (XXY), 0.0922/100; (c) other non-XX, non-XY, excluding Turner and Klinefelter,0.0639/100; (d) Turner syndrome (XO), 0.0369/100; (e) vaginal agenesis, 0.0169/100; (f) classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia,0.00779/10; (g) complete androgen insensitivity, 0.0076/100; (h) true hermaphrodites, 0.0012/100; (i) idiopathic, 0.0009/100; and (j) partial androgen insensitivity, 0.00076/100. The chief problem with this list is that the five most common conditions listed are not intersex conditions. If we examine these five conditions in more detail, we will see that there is no meaningful clinical sense in which these conditions can be considered intersex. “Deviation from the Platonic ideal” is, as we will see, not a clinically useful criterion for defining a medical condition such as intersex.

The chromosomal conditions cited here – Kleinfelter, Turner, etc – do fall within the umbrella term DSD (Differences in Sex Development) but, as Sax notes, are not considered to be ‘intersex’ conditions such that while all ‘intersex’ conditions are DSDs, not all DSDs are ‘intersex’ conditions.

To call this paper a hot mess of fallacious reasoning and blatant cherry-picking is, perhaps, being charitable, given that the authors cannot even stick consistently to their own idiosyncratic definition of ‘intersex’ in deriving their model of a supposedly bimodal sex continuum, fudging or simply omitting anything that doesn’t readily fit their proposed model, notably any kind of quantitative measurements of sex hormone levels.

The graph is not just wrong, it is not even wrong.

… and finally.

A massive thank you to Alex (@alexalicit) for putting me on to the Blackwell paper.

Yes …

What’s that X axis all about!

https://twitter.com/MForstater/status/1045693364115558401?s=19

It is my understanding from 10 yrs of being the mentor and US federally approved caregiver for a young XXY man that the inclusion of those with more or less than two sex chromosomes as being intersex is up for debate. Most XXYs I met pre 2014 we’re trying to decide if they were intersex or not after hearing presentations from intersex groups. Many MDs who work throughout the US with sex-chromosomal variant people consider them DSD because some of them certainly do have mixed genital sets. Most XXYs use exogenous testosterone so they have near normal male levels and do not grow breasts. My friend was among those who had such differences and he considered himself intersex.

Thanks for this analysis. I always wondered where that damn sex spectrum graph came from and now I understand at lot more about this issue.

Really enjoyed reading this, thank you!