It’s not often that a paper in a medical ethics journal manages to generate a major shitstorm but a new paper by Alberto Giubilini (Monash University) and Francesca Minerva (University of Melbourne) has managed to do precisely that and the clue to understanding why is probably obvious from the paper’s title, “After-birth abortion: why should the baby live?”:

Abortion is largely accepted even for reasons that do not have anything to do with the fetus’ health. By showing that (1) both fetuses and newborns do not have the same moral status as actual persons, (2) the fact that both are potential persons is morally irrelevant and (3) adoption is not always in the best interest of actual people, the authors argue that what we call ‘after-birth abortion’ (killing a newborn) should be permissible in all the cases where abortion is, including cases where the newborn is not disabled.

Abstract | Full Paper (open access for the time being, but may require registration later).

To describe the paper as ‘challenging’ may be something of an understatement.

The argument that infanticide may be morally permissible in some situations was one that many found difficult to swallow when it was advanced by Peter Singer in the first (1979) edition of ‘Practical Ethics‘ within a very limited context:

Q. You have been quoted as saying: “Killing a defective infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Sometimes it is not wrong at all.” Is that quote accurate?

A. [Singer] It is accurate, but can be misleading if read without an understanding of what I mean by the term “person” (which is discussed in Practical Ethics, from which that quotation is taken). I use the term “person” to refer to a being who is capable of anticipating the future, of having wants and desires for the future. As I have said in answer to the previous question, I think that it is generally a greater wrong to kill such a being than it is to kill a being that has no sense of existing over time. Newborn human babies have no sense of their own existence over time. So killing a newborn baby is never equivalent to killing a person, that is, a being who wants to go on living. That doesn’t mean that it is not almost always a terrible thing to do. It is, but that is because most infants are loved and cherished by their parents, and to kill an infant is usually to do a great wrong to its parents.

Sometimes, perhaps because the baby has a serious disability, parents think it better that their newborn infant should die. Many doctors will accept their wishes, to the extent of not giving the baby life-supporting medical treatment. That will often ensure that the baby dies. My view is different from this, only to the extent that if a decision is taken, by the parents and doctors, that it is better that a baby should die, I believe it should be possible to carry out that decision, not only by withholding or withdrawing life-support – which can lead to the baby dying slowly from dehydration or from an infection – but also by taking active steps to end the baby’s life swiftly and humanely.

Q. What about a normal baby? Doesn’t your theory of personhood imply that parents can kill a healthy, normal baby that they do not want, because it has no sense of the future?

A. [Singer] Most parents, fortunately, love their children and would be horrified by the idea of killing it. And that’s a good thing, of course. We want to encourage parents to care for their children, and help them to do so. Moreover, although a normal newborn baby has no sense of the future, and therefore is not a person, that does not mean that it is all right to kill such a baby. It only means that the wrong done to the infant is not as great as the wrong that would be done to a person who was killed. But in our society there are many couples who would be very happy to love and care for that child. Hence even if the parents do not want their own child, it would be wrong to kill it.

Giubilini and Minerva’s paper takes Singer’s core argument a stage further, arguing that infanticide may be morally permissible not only where a newborn is found to have a serious, life-limiting, congenital abnormality but in other situations in which abortion is legally permissible:

Euthanasia in infants has been proposed by philosophers for children with severe abnormalities whose lives can be expected to be not worth living and who are experiencing unbearable suffering.

…

Although it is reasonable to predict that living with a very severe condition is against the best interest of the newborn, it is hard to find definitive arguments to the effect that life with certain pathologies is not worth living, even when those pathologies would constitute acceptable reasons for abortion. It might be maintained that ‘even allowing for the more optimistic assessments of the potential of Down’s syndrome children, this potential cannot be said to be equal to that of a normal child’. But, in fact, people with Down’s syndrome, as well as people affected by many other severe disabilities, are often reported to be happy.

Nonetheless, to bring up such children might be an unbearable burden on the family and on society as a whole, when the state economically provides for their care. On these grounds, the fact that a fetus has the potential to become a person who will have an (at least) acceptable life is no reason for prohibiting abortion. Therefore, we argue that, when circumstances occur after birth such that they would have justified abortion, what we call after-birth abortion should be permissible…

…

Failing to bring a new person into existence cannot be compared with the wrong caused by procuring the death of an existing person. The reason is that, unlike the case of death of an existing person, failing to bring a new person into existence does not prevent anyone from accomplishing any of her future aims. However, this consideration entails a much stronger idea than the one according to which severely handicapped children should be euthanised. If the death of a newborn is not wrongful to her on the grounds that she cannot have formed any aim that she is prevented from accomplishing, then it should also be permissible to practise an after-birth abortion on a healthy newborn too, given that she has not formed any aim yet.

There are two reasons which, taken together, justify this claim:

The moral status of an infant is equivalent to that of a fetus, that is, neither can be considered a ‘person’ in a morally relevant sense.

It is not possible to damage a newborn by preventing her from developing the potentiality to become a person in the morally relevant sense.

The reasoning here is sound as long you accept the premise that the moral status of a human being is contingent on the possession of a sense of their own existence of over time (Singer) or the capacity to form ‘future aims’ (Giubilini & Minerva) and – crucially – that we can be certain that a neonate possesses neither of these qualities. On the latter point I’m really not sure that our current understanding of the neurological development of the foetus/neonates is sufficiently well developed to afford us the degree of certainty we’d need to accept the validity of either premises much beyond the point at which the neurological structures which support those capabilities start to develop in earnest, which – fortutiously, so far as our existing abortion law in concerned – occurs during the third trimester of a pregnancy, i.e. from around 25-26 gestation onwards.

Moreover, the argument for permitting euthenasia to be practiced on severely disabled neonates where their is no realistic prospect of a newborn enjoying any significant quality of life is one that need not hinge on the infant’s presumed moral status as a person. Such a decision can be justifed, morally and ethically, as an act of compassion where the alternative, for the child, would be nothing more than a prolonged period of intense suffering prior to their inevitable demise.

Although Giubilini & Minerva’s argument appears, on the surface, to be nothing more than an extension of Singer’s argument, it differs in one crucial respect. In acknowledging that, in our society, there are many couples who would be happy to care fora child that has been rejected by its natural mother, Singer implicitly accepts that the act of rejecting the child severely weakens, if not abrogates entirely, the natural mother’s own moral claim over the continued existence, or otherwise, of the child to the extent that other parties, i.e. relatives, putative adoptive parants and even the state may legitimately assert their own moral claim to the life of the child and overide the wishes of its natural mother.

The resolution of these competing moral claims lies, of course, at the heart of the ethical debate on abortion in which, as the law currently stands in the UK, such that the state can be seen to assert the primacy of its own claim to the life of a healthy foetus at 24 weeks gestation the current upper limit for elective abortions, and at birth where the foetus has a serious congenitial abnormality. If follows, therefore, that those who oppose abortion in most or all circumstances, or who argue for further restriction on the upper time limti for abortion or the legal grounds on which abortion is permitted are, in this context, arguing for an extension of the state’s moral claim to the life of the foetus to the exclusion of the natural mother own claim over the foetus and over her own personal autonomy which, of itself, serves to demonstrate that the anti-abortion lobby’s claim to be ‘pro-women’ is nothing more than an exercise in empty, intellectually dishonest, rhetoric.

Giubilini & Minerva’s own attempt to address the issue of competing moral claims over the life of the neonate is to be found in their discussion of adoption and is, at least as I see, not particular compelling:

A possible objection to our argument is that after-birth abortion should be practised just on potential people who could never have a life worth living. Accordingly, healthy and potentially happy people should be given up for adoption if the family cannot raise them up. Why should we kill a healthy newborn when giving it up for adoption would not breach anyone’s right but possibly increase the happiness of people involved (adopters and adoptee)?

Our reply is the following. We have previously discussed the argument from potentiality, showing that it is not strong enough to outweigh the consideration of the interests of actual people. Indeed, however weak the interests of actual people can be, they will always trump the alleged interest of potential people to become actual ones, because this latter interest amounts to zero. On this perspective, the interests of the actual people involved matter, and among these interests, we also need to consider the interests of the mother who might suffer psychological distress from giving her child up for adoption. Birthmothers are often reported to experience serious psychological problems due to the inability to elaborate their loss and to cope with their grief. It is true that grief and sense of loss may accompany both abortion and after-birth abortion as well as adoption, but we cannot assume that for the birthmother the latter is the least traumatic. For example, ‘those who grieve a death must accept the irreversibility of the loss, but natural mothers often dream that their child will return to them. This makes it difficult to accept the reality of the loss because they can never be quite sure whether or not it is irreversible’.

We are not suggesting that these are definitive reasons against adoption as a valid alternative to after-birth abortion. Much depends on circumstances and psychological reactions. What we are suggesting is that, if interests of actual people should prevail, then after-birth abortion should be considered a permissible option for women who would be damaged by giving up their newborns for adoption.

One of the obvious difficulties with this line of argument is that even allowing for the evidence that some women experience serious psychological problems after giving up a child for adoption one cannot reliably predict, in advance, whether a particular women who may be about to make that decision is likely to experience such problems, anymore than one can reliably predict whether or not a women having an abortion or giving birth with the intention of raising the child is likely to experience psychological problems due to their own experiences, even if the overall level of risk associated with each outcome is known with a reasonable degree of reliability.

Equally, one cannot assume that the risks of psychiatric sequelae assocated with infanticide – sorry, but I just don’t the idea of hiding behind euphemism here – will be the same or similar to those associated with abortion, not least as the evidence from studies of abortion and mental health tend to indicate that the risk of women experiencing significant psychological distress, post-abortion, are mediated by the extent to which they conceive of the foetus as a fully human child as oppose it regarding it an organism that has temporarily taken up residence in their own body- and this is equally true of women who miscarry. In general, the later a termination occurs, whether its eleective or spontaneous, the greater the risk that the women will experience significant levels of psychological distress and, consequently, the greater the risk of subsequent psychiatric sequelae. In the absence of other mitigating factors, which in our society will almost always mean several congential abnormality, one must assume, as a default position, that the risks associated with infanticide will be greater than those associated with even a late-term abortion and significantly greater than those associated with an abortion which takes place during the first trimester.

As unconvincing as I find Giubilini and Minerva’s arguments in relation to adoption it is at least refreshing to see someone acknowledging that there are significant risks associated with giving up a child for adoption, risk that may well exceed, by some distance, the risks associated with abortion, as was noted by Condon (1986), one of the paper’s cited by Giubilini and Minerva:

A most striking finding in the present study is that the majority of these women reported no diminution of their sadness, anger and guilt over the considerable number of years which had elapsed since their relinquishment. A significant minority actually reported an intensification ot these feelings, especially anger (Table I). Winkler and van Keppel reported similar findings with regard to what they termed “sense of loss”, this parameter increasing in 48% of their sample.’ Taken over all. the evidence suggests thai over half these women are suffering from severe and disabling grief reactions which are not resolving with the passage of time and which manifest predominantly as depression and psychosomatic illness.

A variety of factors operated to impede the grieving process in these women. The emotional significance of their loss was not acknowledged by either family or professional persons, who denied them the opportunity and support necessary for the expression of their grief. Intense anger, shame and guilt complicated their mourning, which was further inhibited by the fantasy of possible eventual reunion with the child. Many were too young to have acquired the ego strengths necessary to grieve in an unsupportive environment. Finally, few had had sufficient contact with the child at birth, or received subsequently sufficient information to enable the construction of a clear image of what they had lost. Masterson has demonstrated that mourning cannot proceed in the absence of a clear mental image of what has been lost. There was a clear impression that the grief of many of these women had arrested in the early “searching phase” described by Bowlby. They were desperately searching, not to regain the child per se, but to acquire information which would enable them to build up a picture of the lost child and thereby resolve their grief.

The notion that maternal attachment can be avoided by brisk removal of the infant at birth and the avoidance of subsequent contact between mother and child is strongly contradicted by recent research. I and others’ have demonstrated an intense attachment to the unborn child in most pregnant women. Moreover, evidence supporting Klaus and Kennell’s theory, that a rapid and significant increase in maternal attachment occurs with physical contact in the first 24 hours,17 has recently been strongh questioned.”‘ A current consensus would be that, at best, their theory is unproven.”

Condon J. Psychological disability in women who relinquish a baby for adoption. Med J Aust 1986; 144:117–19. | download

We need to approach Condon’s paper with a degree of caution; it’s over twenty-five years old, the sample group on which its based in small (n=20) although his findings appear to be consistent with a much large study by Winkler and Von Keppel (1983) and research in the general area of maternal attachment and child development has moved on considerable to the extent that thevalidity formative work of Bowlby (referenced above) and others has been significantly challenged. Nevertheless, some thing certain haven’t changed since the publication of Condon’s paper in 1986:

…with the exception of Winkler and van Keppel’s major Australian study,’ the outcome of women who relinquish an infant at birth has received virtually no attention in the psychological, psychiatric or obstetric literature, nor is it usually mentioned in the literature on adoption. The latter tends to focus on the outcome of the child and that of the adoptive parents. This hiatus in the literature probably reflects the misconception that, since relinquishment is “voluntary” and occurs before the woman has bonded to the child, adverse psychological sequelae would be rare.

More than a quarter of century on the literature relating to the outcomes of women who relinquish an infant at birth is still very much ‘on hiatus’ and consideration of the fate of these women, within the public discourse on both abortion and adoption, continues to be as common as rocking-horse shit, regardless of Condon’s striking exposition of the key differences between women’s experiences of relinquishment and perinatal bereavement.

The relinquishment experience differs from perinatal bereavement in four psychologically crucial aspects.

First, although usually construed by society as “voluntary”, most relinquishing mothers feel that relinquishment is their only option in the face of financial hardship; pressure from family or professional persons; the stigma associated with single motherhood or illegitimacy; and a general lack of support. Their perception of “informed consent” is that it is a charade designed to obfuscate society’s guilt at “forcing” them to relinquish.

Secondly, their child continues to exist and develop while remaining inaccessible to them, and may “one day” be reunited with them. The situation is analogous to that of relatives of servicemen ‘missing, believed dead” in wartime. The reunion fantasy renders it impossible to “say goodbye” with any sense of finality. Disabling chronic grief reactions were particularly common after the war in such relatives.’

Thirdly, lack of knowledge about the child permits the development of a variety of disturbing fantasies, such as the child being dead, ill, unhappy or hating his or her relin¬quishing mother. The guilt of relinquishment is thereby augmented.

Fourthly, these women perceive their efforts to acquire knowledge about the child (which would give them “something to let go of’} as being blocked by an uncaring bureaucracy. Shawyer describes poignantly how “confidential files are tauntingly kept just out of reach, across official desks”. Thus, the anger that is associated with the original event is kept alive and refocused onto those who continue to come between mother and child.

I think it fair to say that the assumption that ‘voluntary’ relinquishment of child is relatively risk and consequence free persists to this day as these issues tend to be aired and receive attention only within the context of cases in which children are removed from the care of their natural parent(s) by the state, i.e. social services, and not within the context of ‘voluntary’ adoption.

Regrdless of you feeling about the paper itself, and people can be readily forgiving for finding Giubilini’s arguments challenging, disturbing and eminiently disagreeable, as an ethic paper published with the intent of provoking serious and far-reaching debate on a complex set of ethical questions, one cannot reasonably criticise either the authors, for posing these questions, or the Journal of Medical Ethics for choosing the publish the paper.

As the Journal’s editor corectly notes, many of the arguments here are not at all new or novel save, perhaps, for the paper’s consideration of maternal and family interests and the purpise of the paper is not to advocate any specific policies or alterations in existing legislation based on it author’s line of reasoning:

Many people will and have disagreed with these arguments. However, the goal of the Journal of Medical Ethics is not to present the Truth or promote some one moral view. It is to present well reasoned argument based on widely accepted premises. The authors provocatively argue that there is no moral difference between a fetus and a newborn. Their capacities are relevantly similar. If abortion is permissible, infanticide should be permissible. The authors proceed logically from premises which many people accept to a conclusion that many of those people would reject.

Nevertheless, the reaction to this paper in some quarters has been as predictable as it has been been oppotunistic, ignorant, depressing and thoughly anti-intellectual – in others, including amoungs some members of the medical profession, its provoked a palpably visceral reaction but little by way of reasoned argument that passes much beyond ‘b-b-b-but that’s immoral’ all of which tends to prove, if further proof were needed, that Hume’s arguments on the nature and origins of morality stand on much more solid foundations than those of Kant or of most of the leading lights of utilitarianism.

Both the paper’s authors and the journal have received abusive emails, along with the usual anonymous death threats from fully paid-up members of the 101st Fighting Keyboard (Wingnut Division) and may of the comments that have aired in public are scarcely any better, although the grand prize for unrestrained prejudical lunacy should probably go to the author of the following comment:

“Alberto Giubilini looks like a muslim so I have to agree with him that all muslims should have been aborted. If abortion fails, no life at birth – just like he wants.”

With…

“Here’s the “projected moral status” you comunisti italiani pigs would get: Bang, bang. Drop in toxic waste dump reserved for left-wing contaminants.”

…running a fairly close second.

While we’re on the subject of ‘the stupid… it burns!!!’, our own Poundshop Palin, Nadine Dorries has been busily trying to milk the manufactured furore surrounding this paper for all she get out of it, running the full gamut of rational ethicial discourse from ‘A’ to ‘Aaaaawww… look at the wickle baaaabbbbby!!!’.

For once, I’m not inclined to dignify Dorries’ febrile brand of arse-gravy with a detailed commentary. New Humanist have already taken care of her abject, if award-winning, inability to understand what an association fallacy is, let alone how to avoid using one and The Sun’s suggestion that the paper amounts to a call for the legalisation of infanticide is a complete nonsense, even if they did manage to provide an accurate description of Dorries as ‘a leading anti-abortion campaigner’.

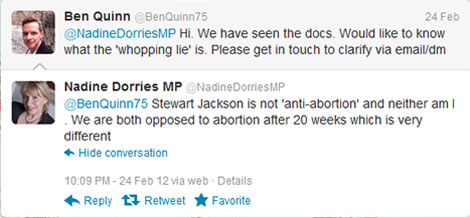

However, I can’t leave this subject without puncturing at least one of Dorries’ delusional bubbles, one that – in this case – stems from an twitter exchange with the Guardian’s Ben Quinn on 24th Feb in relation to this article on the impending consultation on pre-abortion counselling.

As usual, Dorries was being rather economical with the truth. When votes were taken on the options of reducing the upper time limit for election abortions at the committee stage of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill in 2008 – amendments dealing abortion and some other issues were put to the Committee of the Whole House rather than the more usual Public Bill committee – Jackson voted to reduce the upper limit to 16 weeks, not just 20 weeks.

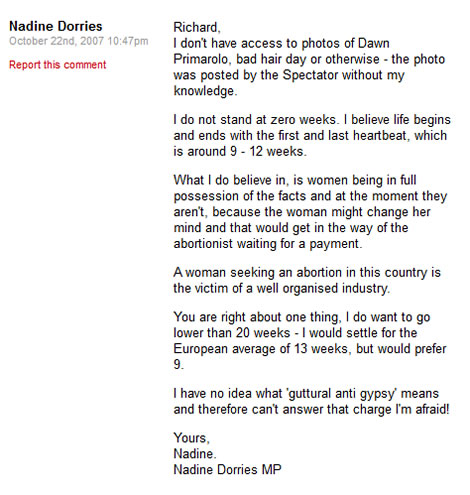

As for Dorries, she voted to reduce the upper limit to just 12 weeks, the shortest option that was put to a vote. However, a few months before these votes were taken, Dorries left the following comment under one of her own typically delusional articles at the Spectator’s CoffeeHouse blog.

It perhaps goes without saying that Dorries even made glaring mistakes in that last comment.

A foetal heart beat can usually be detected at around 6 weeks gestation, not 9-12 weeks, at which point the fetus itself is only four weeks old, and the 13 week ‘European average’ is the average upper limit for abortion on request and without any requirement to show medical grounds for the abortion, a system we don’t have in the UK – and which Dorries opposes anyway. Most European countries that have a secondary limit for therapeutic abortions, i.e. abortions carried out on medical grounds, which can extend right up to the point of birth, depending on the exact grounds for which the abortion is sought.

3 thoughts on “The Return of the Infanticide Debate”